At the beginning of his rule, King Henry VIII (1509-1547) of England was zealous of the traditional Christian faith, the Catholic faith. In 1521, he wrote an “Affirmation of the Seven Sacraments” against Luther’s doctrine, which made Pope Leo X bestow upon him the title “Defender of the Faith”. In 1509, he wed Katharine of Aragon, his brother Arthur’s widow; he had several children from this marriage, but they all died very young, and only Mary Tudor survived.

In love with a lady of his court, Anne Boleyn, and obsessively worried over the lack of a male heir, the king sought to dissolve his marriage to Katharine by alleging it was null because the betrothed were first degree in-laws. This was a false pretext, since Pope Julius II, at the request of the king himself, had granted him dispensation as required by canonical law for him to marry Katharine; besides, Henry only brought up such “impediment” after eighteen years of married life.

In January 1531, the Pope forbade Henry from marrying again for as long as the case would be under examination by a panel of cardinals charged with judging the matter. Seeing that there was little hope of obtaining the annulment, he decided to request the dissolution of his marriage from the hierarchy in England. On the other hand, Thomas Cromwell, an obscure lawyer who had gained a large influence over the king, advised him to break up from Rome following the example of the German Lutheran princes. In February of that same year, a clergy assembly proclaimed Henry “Supreme Head of the Church of England”, although under a “to the extent permitted by the Law of Christ” clause.

In 1532, the king elevated the priest Thomas Cranmer, who had been in touch with Lutheranism during a trip to Germany, to the archbishopric of Canterbury, the primate see of England. Cranmer accepted to declare the king’s marriage null, and so Henry VIII married Anne Boleyn in 1533. The Pope responded by excommunicating the monarch and declaring his marriage to Katharine valid.

The schism was in the offing: in November 1534, the English Parliament voted the “Supremacy Act”, which proclaimed the king the “sole and Supreme Head of the Church in England”; any subject who did not recognise the Act would be punished by death. The large majority of the clergy submitted, perhaps because they were used to the idea of a national Church and fairly mundane. But a number of laymen, members of the monastic community and clergymen resisted, even to the point of martyrdom, among them the former Lord Chancellor and humanist Thomas More and the bishop John Fisher. The persecution of the Catholics began; many monasteries were closed, relics and images were profaned and destroyed. In spite of the schism and of Lutheran pressure, the king still intended to keep the Catholic faith in England “whole”; he fought both the adherence to the Pope and the Continent’s religious innovations.

The strengthening of Anglicanism imposed, in England, the existence of two very strong religious factions with great capacity to influence royal decisions to suit their purposes.

The following reigns were marked by alternating religious persecutions, particularly Mary Tudor’s of the protestants and Elizabeth I’s of the Catholics, through the institution of the “Uniformity Act” that proclaimed her as Supreme Head of the Church.

Her successor, James I, issued a proclamation upholding such Act and others against the Jesuits and seminarians, and intensified the religious persecution of the “papists” who recognised the King as sovereign of the Nation but not as sovereign of the Church.

It was within this context of persecution that the Catholic Church decided to found seminaries to train Catholic English priests, “papists”, outside England.

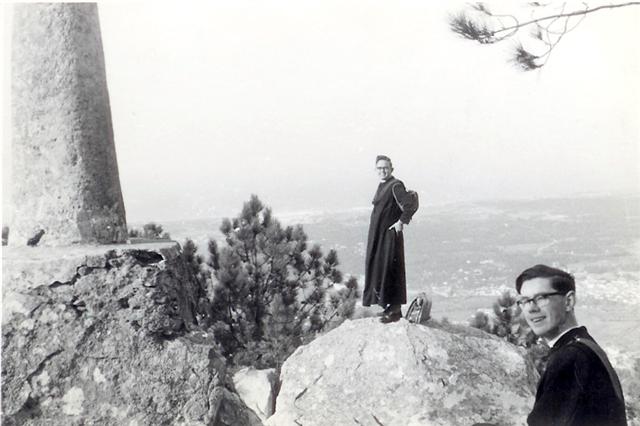

Dies Non - A day out!

In 1621, forty-one years after the Alcazarquivir disaster, Philip III, Philip IV of Spain, reigned over Portugal. Europe was fighting the Thirty Years War opposing, in Austria, Catholics and Protestants. In England, under the reign of James I, the persecution of Catholics went on.

Philip II of Spain had already authorised the creation, in Douai, of an institution to harbour young dissidents of the Anglican religion who wished to receive a Catholic education outside England. The success of Douai caused it to become the “Mother House” of other similar institutions, made in its image, such as the ones in Rome (1579), Valladolid (1589), Seville (1592) and subsequently Lisbon.

The privileged location of Lisbon permitted it to act as a transit emporium for numberless ships circulating between Northern Europe and Southern Europe and calling this port, some of them loaded with goods brought from India, Africa and America, and also made the circulation of people from varied provenances easier.

The Rosary Walk

A lot of Englishmen with strong commercial interests in the city lived in Lisbon. Many arrived fleeing from religious persecution victimising them in England. One of those Englishmen, father Nicholas Ashton, the chaplain of the English Catholic community in Lisbon, strived to make the foundation of an English seminary possible, and even acquired a house for such purpose. Before his death, Father Ashton charged his successor, Father Newman, with pursuing such intent. As the Rector of the English Residence in Lisbon, Newman made acquaintance with D. Pedro Coutinho to whom he imparted this plan. The circumstance of Newman being the interpreter of the Inquisitor General in Portugal may have contributed to the authorisation by King Philip IV of Spain for the opening of the College and its subjection to the orders of the Inquisitor.

D. Pedro Coutinho was the descendant of a nobleman of the court of D. Afonso Henriques, to whom the first King granted his name after the conquest of the enclosure (Couto) of Leomil from the Moors. The father of D. Pedro Coutinho perished in Alcazarquivir, and three of his brothers lost their lives while serving in the Portuguese colonies.

In order to institute the seminary, D. Pedro Coutinho donated a few houses he owned on St. Catherine’s hill, Bairro Alto, in Lisbon. Some such houses were intended for lease so that the rent would contribute to the College’s sustenance funds. In exchange for his donations, D. Pedro tried to ensure that the College trained missionaries originating from the English Catholic aristocracy, who, once ordained, would return to England there to reinstate the “true faith”.

College Football Team

Inter-seminary football match!

D. Pedro Coutinho sought by all means to guarantee the exclusion of the Jesuits from the project and to ensure that the College be run by the English secular clergy, unlike all other Colleges outside England. This aversion to the Jesuits was in contrast to the dominant position among the Portuguese aristocracy, who clearly favoured the interests of the Society of Jesus.

The true reasons for this decision remain a mystery. However, D. Pedro’s intransigence as to this matter was such that he reacted violently to the introduction of the Humanities in the original studies plan of the College, and he had a heated polemic with the English Chapter on this matter.

During a tumultuous meeting with the College Superiors at D. Pedro’s in Alfama, in view of the British clergymen insistence on intellectual, not merely spiritual, training for the students following the Jesuit educational guidance, D. Pedro threatened to expel the students from the College, thus showing that he considered the College as his own. Excitedly, he renounced God and refused his place in Heaven.

D. Pedro Coutinho died in April 1638. Before that, he made another donation to the College requesting that three daily masses be celebrated for the rest of his soul. He wished this request to be perpetually satisfied by the College.

His funeral was attended by an unusual number of Lisbon common people and aristocrats. Also present were the religious communities, especially the secular clergy, and very poor people whom he had helped. His body was buried in the Franciscan Church of São José de Ribamar, of which he was also a benefactor.

Christmas Time

The Portuguese nobleman soon offered to erect, at his expense, a college for the education of the English secular priests and to make available houses and land of his property to make it happen. Newman got from his Superiors in England full powers to execute the project and, in August 1621, he left to Madrid in order to apply for Philip IV’s authorisation.

Essentially, the petition ran thus:

“... I present a few of the reasons for Your Majesty to grant us a licence to found an English seminary in Lisbon, in imitation of the Douai English proto-seminary, and I merely add that this seminary will be subordinated to the person of the Inquisitor General of the Kingdom of Portugal as requested and desired by its founder himself… the intention is to educate priests so that they will be able to preach the holy Catholic faith to the English heretics… I remind Your Majesty that the Douai seminary has already given over a thousand labourers for this holy vintage and that, for preaching the Catholic faith in England, one hundred and nine or one hundred and ten of them have been subject to martyrdom… the founder promised this English seminary to the Catholic bishop prelate of England in Lisbon, and for its foundation he immediately gives five thousand crusados and a further five hundred crusados of rent, other than what the seminary will inherit upon his demise...”

To this petition, Philip of Spain replied by Royal Charter dated the 3rd December 1621, the charter authorising the foundation of the College:

“I, the King, make it known to whom may see this charter that as far as the request of the English priest William Newman is concerned… about the seminary that in this said city a few persons devoted to the service of Our Lord and to accrue their holy Catholic faith wish to found with their church there to harbour the said English Catholics or priests and create subjects to be sent to the said Kingdom… and considering the alleged and advised by Francisco Rebello Homem, esquire, a civil magistrate of this city, who asserted that this is a very profitable work for the good of the Christendom of the said Kingdom: I deign and it is my pleasure to grant licence for the said seminary to be founded and goods be provided for its sustenance…”

On the 29th September 1622, Pope Gregory XV declared that all privileges enjoyed by other similar Institutions be granted to the College.

In the College garden.

The College Avery

Perhaps by chance, which is the name given by disbelievers to divine intervention in the matters of man, the College received the name of the apostle on whom the true church was erected, also the name of the Portuguese noble benefactor. The name of St. Paul was associated probably due to the significance of the apostle of the Gentiles for the English people. Peter and Paul, the simple faith and the organising reason. What better patronage could this College wish, a College destined to educate men fishers on the land where the king’s temporal power permitted him to proclaim himself as defender of the faith and governor of the church?

Thus were created the conditions for the erection of St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s College, called by the English the Lisbon College, but which the people of Lisbon fondly called Convento dos Inglesinhos (Convent of the “Inglesinhos”). Wrongly, it is true, because it was never a convent. However, the scarcity of the appearance of the students on the outside and the “reclusion” imposed on them by a severe training may have been the reasons for such designation. Although we refer to the institution as College, why would we not follow the popular designation, undoubtedly more affectionate and fond, evidence of the feelings the people of Lisbon devoted to the College all along its almost 400-year existence? The Portuguese nobleman soon offered to erect, at his expense, a college for the education of the English secular priests and to make available houses and land of his property to make it happen. Newman got from his Superiors in England full powers to execute the project and, in August 1621, he left to Madrid in order to apply for Philip IV’s authorisation.

Essentially, the petition ran thus:

“... I present a few of the reasons for Your Majesty to grant us a licence to found an English seminary in Lisbon, in imitation of the Douai English proto-seminary, and I merely add that this seminary will be subordinated to the person of the Inquisitor General of the Kingdom of Portugal as requested and desired by its founder himself… the intention is to educate priests so that they will be able to preach the holy Catholic faith to the English heretics… I remind Your Majesty that the Douai seminary has already given over a thousand labourers for this holy vintage and that, for preaching the Catholic faith in England, one hundred and nine or one hundred and ten of them have been subject to martyrdom… the founder promised this English seminary to the Catholic bishop prelate of England in Lisbon, and for its foundation he immediately gives five thousand crusados and a further five hundred crusados of rent, other than what the seminary will inherit upon his demise...”

To this petition, Philip of Spain replied by Royal Charter dated the 3rd December 1621, the charter authorising the foundation of the College:

“I, the King, make it known to whom may see this charter that as far as the request of the English priest William Newman is concerned… about the seminary that in this said city a few persons devoted to the service of Our Lord and to accrue their holy Catholic faith wish to found with their church there to harbour the said English Catholics or priests and create subjects to be sent to the said Kingdom… and considering the alleged and advised by Francisco Rebello Homem, esquire, a civil magistrate of this city, who asserted that this is a very profitable work for the good of the Christendom of the said Kingdom: I deign and it is my pleasure to grant licence for the said seminary to be founded and goods be provided for its sustenance…”

On the 29th September 1622, Pope Gregory XV declared that all privileges enjoyed by other similar Institutions be granted to the College.

Perhaps by chance, which is the name given by disbelievers to divine intervention in the matters of man, the College received the name of the apostle on whom the true church was erected, also the name of the Portuguese noble benefactor. The name of St. Paul was associated probably due to the significance of the apostle of the Gentiles for the English people. Peter and Paul, the simple faith and the organising reason. What better patronage could this College wish, a College destined to educate men fishers on the land where the king’s temporal power permitted him to proclaim himself as defender of the faith and governor of the church?

Thus were created the conditions for the erection of St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s College, called by the English the Lisbon College, but which the people of Lisbon fondly called Convento dos Inglesinhos (Convent of the “Inglesinhos”). Wrongly, it is true, because it was never a convent. However, the scarcity of the appearance of the students on the outside and the “reclusion” imposed on them by a severe training may have been the reasons for such designation. Although we refer to the institution as College, why would we not follow the popular designation, undoubtedly more affectionate and fond, evidence of the feelings the people of Lisbon devoted to the College all along its almost 400-year existence?

What did the future missionaries study at the English College? What were the disciplines that occupied their days and a portion of their short nights?

English colleges run by the Jesuits, Rome, Valladolid, Seville and Madrid, adopted the studies plan of the schools of Humanities, Philosophy and Theology. They studied St. Augustine’s and St. Thomas Aquinas’s Scholastic Theology, Aristotelian Philosophy and the Holy Scriptures. As to the Humanities, these were composed of the seven Liberal Arts: grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy.

In spite of the abovementioned opposition of D. Pedro Coutinho to the Jesuits, the Lisbon English college followed the same learning procedures as their congeners in the peninsula. The main teaching method of the Bible text was dictation. The Master of the Holy Scriptures would dictate a passage from the text, and the students would reply commenting. The studied lessons and verses were coded in an index format for easy future reference, in order to serve as a vade mecum for the future missionaries. The New Testament, the Gospel of John and the Acts of the Apostles were recited in Latin by the Master, who commented on certain passages according to the liturgical calendar or the instructions of the President of the College. The students would take down note of the comments for private use and reflection.

In spite of the reclusion as for a monastery, the College sometimes communicated with the city of Lisbon, by inviting clergymen of other orders and of the Archdiocese of the Portuguese capital to attend the public argumentations on Philosophy and Theology that were carried out by the students and coordinated by the Principal. Such argumentations were announced all over the city, but one of the most important religious confessions of the time never showed up for the debates: the Jesuits. It is obvious that these debates were intended to show the merits of the education provided at the College and the superiority of its students over those of other colleges, such as the Irish St. Patrick’s College and the Dominican Corpus Christi College. The students of the Jesuit college of S. Roque, Casa Professa, were always conspicuous by their absence.

The audience also comprised laymen of the Portuguese nobility, including members of the royal family. And so the relations between the college and the city were restricted to these encounters, the college remaining a closed institution that strictly separated sacred from profane.

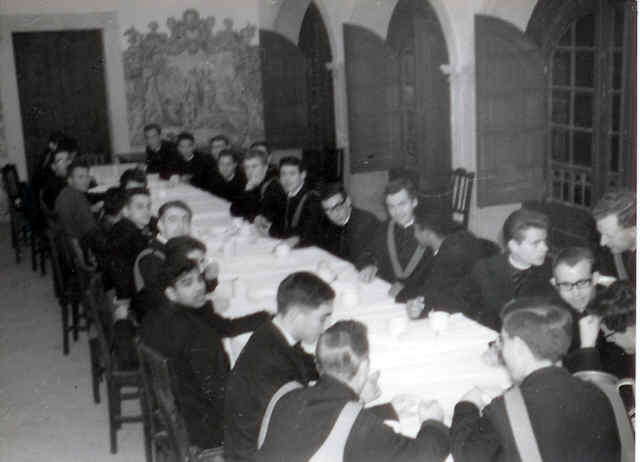

While the food for the spirit was sumptuous, the food for the body was more frugal. Save for the absolute fast on Fridays, each student would receive, at 8 a.m., for breakfast, 90 grams of bread, 30 grams of butter and water. Called at 4 o’clock, bread and water was how the students broke their fast. They had lunch at 11 o’clock, 200 grams of meat, and for supper, at 7 p.m., they received another 200 grams, but only when the college’s resources so permitted. This last meal of the day was, thus, considered, a luxury. Lunch and dinner were served with a small portion of wine collected just after fermentation, with the lowest alcohol graduation.

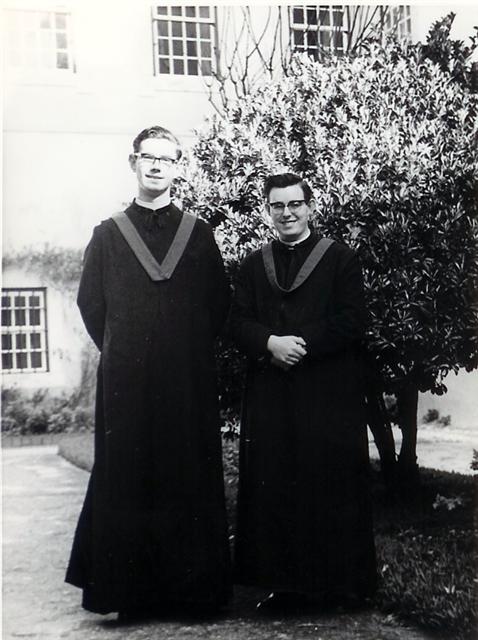

Their clothing customs were simple as well: a cassock made in a lustrous black material, a sash and a biretta. On ceremonial occasions, when in public and outside the College facilities, they wore, over the cassock, a large sleeveless habit, which was joined by a red cloth stripe shaped as a paddle and which extremities fell behind the shoulders while the middle part was arched on the chest. The uniform of the superiors was the same as the students’, except for the cassock, which was made in serge, and the habit that was replaced (when in public) by a long black cloak in that same material.

The Refectory

The harsh rule imposed on daily life at the College was interrupted once a year, during the month of September, an occasion when the students would move to a farm, Quinta de Pêra, on the Tagus south bank, in “Capa Rica”, where they would devote themselves to the contemplation of the landscape during the long walks they went on stimulated by the Estremadura plain. They called those three weeks during which they stayed there “Quinta Time”, a time of idyll, when the world seemed perfect and the days passed full of life, wild flower scents and bird singing. Sea swimming was particularly appreciated by the young Englishmen, little accustomed to such warm mild waters in their country of origin. This farm had been donated by Francis Nicholson, who, as a friend of Queen Catherine of Braganza, accompanied her during a visit to Portugal in 1692. In addition to this property, he made several donations in cash to the College to acknowledge his gratitude for his conversion to the Catholic faith.

The relationships with the Braganza dynasty, as from the 1640 Restoration, were always close and favourable to the designs of the College. After the marriage of Catherine of Braganza to the English monarch, they attained their best period. England recognised the Portuguese independence, and John IV undertook to support the College with funds similar to those previously dispensed by Philip IV of Spain. Such funds consisted in 500 thousand reis each year, added by, should the need arise, a supplement of around 200 thousand reis. In 1702, the administration obtained that the Portuguese crown grant the College exemption from paying the tithe, and they saw their annual funds increased to 740 thousand reis in the next year.

The reputation of the College as a centre of academic excellence and its relevance as an English institution in Lisbon attracted patronage from varied sources. Pedro da Costa and Maria de Oliveira Leitoa, for instance, two wealthy Portuguese, transferred important funds to the College in exchange for daily masses for their special intention. Several brotherhoods were created, such as the Brotherhood of the Blessed St. Thomas of Canterbury, archbishop and martyr, in 1657, and the Brotherhood of the Sacred Apostles St. Peter and St. Paul, in 1649. The Rev. Watkinson, an administrator of the College, was granted the ecclesiastic authority’s permission to hear the profession of English and Portuguese Catholics within the Lisbon diocese. Many Portuguese noblemen and aristocrats assumed that authorisation, and elected him as their confessor. This contributed to a large extent to strengthen the ties between the College and the Portuguese high society.

Masses celebrated at the Brotherhoods at the time of the religious feasts gave a fair return to the College; a Requiem Mass celebrated in 1672 cost 17 thousand reis, an equivalent to the budget of half a year support for a student. Among many other members of the high nobility, the Count of Castelo Melhor, the Counts of Merinho Mor and Vila Nova and D. António Luís de Távora were some of the patrons of the College.

In 1679, Pope Innocent XI granted the College the privilege of being considered as a High Altar of Christ on the Cross, Cappellam Collegii Anglorum Civitate Ulixbonem. Any citizen of Lisbon having a Requiem Mass be celebrated at the altar would gain full indulgence to the benefit of their relatives who were benefactors or patrons. A year later, Innocent XII granted the College a similar privilege: anyone visiting the altar of St. Thomas on the day of the saint’s feast would gain full indulgence.

Many other English catholic priests ordained at the College contributed to the moral, religious and intellectual reputation of this Institution and to the high regard in which kings, popes, noblemen and learned men held this community all along its existence. One might say that the Catholics in charge in England selected from the Cambridge and Oxford Universities their best young men to be trained in Lisbon, thus preserving them from the persecutions to which they would be subject in their home country. Once in Portugal, they would switch their family name to another for as long as they were studying or evangelising, so that they could not be identified and persecuted.

The austerity of the morals to which students and teachers submitted every day at the College and the strict administration of the sparing means available shaped the character and disciplined the body of the young Englishmen, leaving their spirit free of the ephemeral pleasures of the flesh.

The influence of many “Inglesinhos” (little Englishmen) on the Portuguese social and cultural life was considerable. Some distinguished themselves for their courage, others, for their intelligence and for their availability.

The first buildings acquired by D. Pedro Coutinho, in 1622, with the intent of erecting the College had no comfortable physical conditions to welcome the first students. Fitting and enlargement works were immediately started, but they took around 5 years to be completed, although there was just one floor then. The church took another 2 years to complete.

D. Pedro Coutinho also donated a few houses which rents would permit ensuring the subsistence of the College. Misericórdia (an Institution established by Queen Leonor in 1498) had the charge of managing the rents in perpetuum and had the obligation of keeping the College building in good condition for as long as it would operate within the purposes for which it had been created.

Up to the beginning of the 18th century, only a few conservation works had been carried out. The petition to rebuild the College was sent to Misericórdia in July 1709, signed by the Principal, Rev. Edward Jones, and by the Superiors of the College. It mentioned “the state of degradation of the dormitories and church” as a premise for such institution to comply with the will of the founder in the preservation of the building.

Misericórdia acknowledged the Patronage but ignored the content of this petition by claiming that the funds bequeathed by D. Pedro Coutinho served merely for the upkeep of the College and its students.

The need for works at the College was such that the Superiors were forced to go to court to request that Misericórdia either comply with its duties or waive its Patronage rights. Meanwhile, they reached a deal whereby Misericórdia waived half its rights over the assets bequeathed by the founder, and any reconstruction works would be the charge of the College Superiors.

Following this agreement, Father Jones, through his personal funds, money received from England, from English residents in the city and from a contribution by the Inquisitor General, King John V and many Portuguese noblemen, started the construction of the foundations of the new College on the 14th June 1714.

The sums obtained proved to be insufficient to complete the work, and the roof would only be laid in 1727. The interior was unfinished and in such a rough imperfect state that the Convent was called the “Lisbon Barn” for some time.

Other than the church and the belfry, which had been merely superficially recovered, the new construction withstood the 1755 earthquake.

In 1776, Father James Barnard was elected President, and he tried to reconstruct the College’s finances. He promoted an audit aimed at repairing the consequences of a negligent management by his predecessors and started handling the accounts in a mercantile and very strict manner. Preston and Allen endeavoured to procure funds. To recover and enlarge the building, which showed traces of the earthquake occurred 21 years before leaving it in a deplorable condition, was defined as a priority.

Between 1777 and 1780, the whole building was renovated thanks to the generous donations made by Bishop Challoner to show his gratitude to Father John Gother, who had been educated at the Lisbon College and by whose intermediary the bishop had been converted to the Catholic faith.

The Lisbon College acquired extreme relevance after the Jesuits were expelled from Spain, and as a result the management of the Madrid, Seville and Valladolid colleges went to the Secular Clergy following the example of Lisbon. Many of the priests educated in Lisbon were sent to those institutions where they applied the knowledge and experience gained at the College.

At the end of the 18th century, as a result of the French Revolution, the Douai college as well as all other Spanish colleges were eventually closed down. It was decided that the Lisbon College should be enlarged and prepared to absorb the students of those other institutions, approximately 40, their Superiors and Masters, with comfortable but simple accommodations.

It was also by this time that the Observatory was erected, a place from where, according to Father Allen, one can see one of the best views in Europe.

In 1814, as the Peninsular War ended, peace between England and France was re-established. The English troops stationed in Lisbon were called back. On the 29th June of that same year, St. Peter and St. Paul day, after 4 years of no religious activity, Mass was again celebrated at the College church. The small-sized church facilities had the reputation of being the worst in Lisbon, it being even dangerous to remain under their roof.

The lack of financial resources kept postponing the decisions of building a new larger church consistent with the new College building, capable of comfortably receiving the students, Superiors and all those who came to the church. Father Buckley and father Hurst undertook to make small repairs as required for the preservation of the building. A new roof was made above the old altar and the old floor tiles were replaced by a beautiful wooden floor. The walls were decorated and the entrance door was replaced by a wooden one. Railings were placed at the centre of the church to separate different areas, with benches for College members and another area for the congregation. During the period when the works were being carried out, mass was celebrated in the arch room, now closed with glass doors separating it from the garden. Such works can still be seen today.

In 1857, two benefactors, D. Joana d´Araujo Carneiro d´Oeynhausen and Rev. Jeronimo da Mata, Bishop of Macao, provided the College with resources that permitted enlargement works to be carried out, which would be completed on the 18th December 1858, at which time the choir was built. However, it was only in 1898, with a sum donated by the Apostolic Notary, Rev. Monsignor James Lennon, a former Inglesinho of the Lisbon College, that the church was entirely decorated and made to look as it now looks.

The last president of the English College - the Rt Rev Monsignor Jim Sullivan - receiving first blessing of newly ordained.

The influence of the exemplary presence and life of the “Inglesinhos” in Lisbon went on until 1973, the year when the College was closed down. The reasons for its foundation had vanished a long time ago.

The Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 had ensured religious freedom as to the catholic faith in England. However, the College had built such a high reputation as a teaching and training establishment for future priests that the Superiors, in London, kept its tenure for a further 144 years.

On the 4th of December 1973, Rev Monsignor James Sullivan, the last principal, before closing down the College, requested from the Municipality of Lisbon information “on the conditions for him to order the preparation of a plan for new buildings intended for housing or offices or mixed use and complementary services.” The intention of preserving the noble building by giving it some use that would keep it alive was obvious on the principal’s request.

This nobility, based on four centuries of a wealth of culture, renders this building into a true icon of the great Portuguese houses, because, although it is known as the College of the Little Englishmen, it is Portuguese by its name, by the city of Lisbon that sheltered it and by the Portuguese history it accompanied and in which it took part.

Ordinations to sub-Diaconate

Ordinations to the Diaconate

Ordinations to the Priesthood.

The newly Ordained with

His Eminence Prince Maximilien Louis Hubert Egon Vincent Marie Joseph

Cardinal von Fürstenberg-Stammheim (23 October 1904 - 22 September 1988).

Apostolic Nuncio to Portugal.